I want to talk about innocence and blame. I think both are fundamentally flawed and our belief in them compounds rather than lessens our miseries, especially in how they leave us susceptible to the politics of alienation and retribution, resulting in terrible justice policies, among other things.

People routinely say “everything happens for a reason,”1 seemingly asserting that there’s something special about this arrangement of things.2 That’s as it may be. Here I take the standpoint that “everything happens for a cause”. Hop on board the things-have-causes axiomatic train and let’s explore some of the implications for how we think about innocence and exoneration, blame and retribution.

This song played on the radio all the time when I was in Grade 9 and I thought of the girl I loved3 at the time and how after something happened to her we could lay on a grassy field and hold hands. It even got to the point where I wished something would happen to her, so this could happen. Though I’d probably be no more likely to show my feelings then than normally, so if my wish had come true because I made it, it would have been both wretched and futile.

For a while after this, being the concrete sort of thinker I was4, I wanted to think of innocence as something real. Maybe it was something I still had, but that I’d lose later.5

What is innocence? A state where you should not be blamed for something. Okay, but why not?

You couldn’t have understood.

Couldn’t have? That’s quite an assertion. How do you know that? I’ll agree that it’s more likely that a kid doesn’t understand x, but you have to test it. Saying that the kid can’t understand x is demeaning. (Okay, it’s probably not demeaning to babies to say they can’t understand nuclear physics, but you can still ‘test’ this: knowing that you haven’t seen them reading or mathing much yet, you can be nigh-absolutely confident that they can’t, or at least that all the babies you’ve ever met can’t.) Anyway, here’s the story of a Korean fellow who was solving differential equations at age seven.

And then there’s the self-fulfilling prophecy: We go out of our way to isolate kids because we believe they can’t possibly understand and thus we guarantee they can’t possibly understand.6

There’s an idea that not understanding x is wrong and doing it is not as bad as understanding x is wrong and still doing it. Gosh, well, it would be nice if we were consistent with that principle. Yes, for practical reasons, ignorantia juris non excusat must be so, else anyone could just claim they didn’t know about the particular law. But in the ideal case, where the person really doesn’t know, there is something about bringing down the force of the law that feels wrong. And I’m for this feeling wrong. But it doesn’t seem to be a factor very often except with very young children.

For truly serious stuff (not, for example, idiosyncratic traffic rules in certain jurisdictions, and I’m also not counting idiosyncrasies about where lines are drawn on stuff that’s taken seriously – in fact, that’s part of the categorical thinking I mean to critique), this would seem to be pretty rare, though I’m open to findings to the contrary. If someone with ordinary mental faculties who wasn’t raised in a cupboard managed to avoid learning that killing7 other people is generally wrong8, it would be a marvel of sorts.

There are two kinds of parents9: Those who have half a clue about what their kids are like, and those who wilfully delude themselves. I’m joking a bit about the ‘wilful’ because if I’m going to demolish free will10 maybe I should not even use the word ‘will’ and I should probably call it ‘instinctive-determined’ delusion.11

The parents who have half a clue about what their kids are like will know that they do lots and lots of things about which they know better, often at whatever opportunity they can get. I say this with all the love and appreciation in the world – I really love kids – and yet it remains that they are scheming parasites. They are generally a far cry from being little angels, though they’ll certainly have their moments that make you go “Awwww!” And it’s good for them that they do, else they might more often find themselves playing an impromptu wilderness game of “Find the City Mom and Dad Drove To”.

I’m not blaming them – it makes sense for them to be scheming parasites virtually all the time, assuming you haven’t taught them how to milk a metaphorical or literal cow, and even after that they’re still going to take more than they give until you’re old and grey (and in this economy, sometimes “and beyond…”). Although if they keep this up forever, they’ll confound expectations:

Should you give in to kids 100% of the time? No, that’s lunacy: the kids have no incentive to stop taking once objectively satisfied. (Neither do adults, really!) You’ll sometimes daily hourly every 30 seconds have to put on the brakes. It’s your job to provide the necessities. This should include a bit of cow-milking and a bit of fun, too, but if you want to put your foot down on giving your hard-earned real-world money to morally bereft shysters for the privilege of flipping a few bits on the server of the latest insidious narcissism-indulging money-leeching social “game”, I am totally in your corner. Not that I expect we’d win, but it’s a hill worth dying on.

Kids can develop more self-control as their brains and experience banks develop, though it’s not a guarantee – if there’s no incentive for a kid to develop self-control, they never will. You won’t find me preaching “spare the cattle prod and spoil the child”, but I will suggest “do everything according to what your child wants and you will probably spoil the child”. Of course, good socializing, from or in spite of parents, is important. And there’s that d-word: discipline. I’m just speaking in common-sense terms – I’m not a pediatric neurologist or anything like that, and as of this writing I’m not a parent nor do I have offspring.

But I was a kid myself, and I perceived stuff and thought about things, and I remember some of it. The blame and punishment stuff bugged the heck out of me then, especially in the stultifying context of grade school, and it bugs me again now, but at least now I can name and describe the irritants.

What I want to ask is, where is the space for innocence?

You have kids, who very often know better, who do the wrong thing anyway. Yet, legally, they’re angelic cherubs. Then you have adults, who almost always know better, who do the wrong thing anyway. And, legally, they can get the full opprobrium of your Law & Order™ types.

And the difference between these two categories is an arbitrary line.

Maybe there’s some extra plasticity for kids and teens, maybe you feel like there’s more potential for rehabilitation. And then to help this along you provide anonymity and you erase their record and it’s almost as if it never happened.

Maybe there’s less plasticity for adults™, maybe you feel like there’s less potential for rehabilitation. I’m not saying this is wrong, but it’s funny how this is a self-fulfilling prophecy because we go out of our way to plaster names and pictures hither and yon and create a permanent record that will follow them all the way to the depths of hell and it will never be as if it never happened. (And our CPC-run government, for its part, passed new rules to make it much harder and in many cases impossible to apply for pardons.)

Our beliefs about blame and innocence are reflected in our justice system. There are layers upon layers of categorical thinking. We have a trinary system of offences based on age – before age 12: not criminally responsible, then the Youth Criminal Justice Act applies for 12-18, then regular adult.

It’s well-meaning, yet, as with any categorical regime, it could lead to absurd results. Let’s say a teenager gets into a fight and stabs someone. The stabbed person dies. Let’s say it’s a charge of manslaughter. If they’re eighteen less a day, they may get all the protections of the Youth Criminal Justice Act. If convicted, possibly a three year maximum sentence. If it’s their eighteenth birthday – hey, maybe it’s Alberta and they had a few dozen libations – they could get a life sentence, and with a life sentence 25 years will pass before they’re even eligible for parole. Would the same judge swing the sentence that broadly? Perhaps not. But I’ll bet that the person who turned 18 is much more worried about getting a competent, present lawyer and a sympathetic judge! Hopefully he hasn’t been in trouble before.

Sometimes teenagers are given adult sentences, but I’ve never heard of the reverse ever happening.

It could be worse. In the United States the question has been whether or not to execute based on age. In 2005, their highest court held that it is contrary to their constitution to impose capital punishment for crimes committed while under the age of 18.

But here’s my point: Why does a child get credit for not developing, but an adult has no excuse? Why didn’t the adult develop? Or if developed, why no worky? Pardon the straw man: What magic thing are you expecting to see when the human passes through the child/adult legal line? If there’s something there in new adults, it’s even harder to observe in them than their voting!

I have great respect for the idea that we inhibit the stabby-stabby by having strong sanctions against it. Just because I don’t believe in blame doesn’t mean I don’t believe in punishment, but the points of it should be deterrence and protection12 (and take a swing at rehabilitation while you’re at it). Simple retribution is just as base as the stabby-stabby in the first place.

To me, this is the math of misery:

Misery + Misery = 2 * Misery

Absent a post-Hammurabi legal system, perhaps there’s something to be said for simple reciprocal misery, but why enshrine that if you can do better? Certain religions go out of their way to establish the opposite – turn the other cheek, forgive, forgive!13 Somewhat ironically, one that does is one that is nominally adhered to by much of the CPC and many of its supporters.

I think in order to actually blame, you have to attribute a wilfulness to keep in your brain the weather patterns to do the bad thing. But even then you could ask, why would you have the wilfulness to have the weather patterns to have the wilfulness to have the weather patterns…

There’s no place to stop, except by exhaustion or by decree. Free will is turtles all the way down.

As Sam Harris and Richard Dawkins discuss in their 2011 talk, “Who Says Science has Nothing to Say About Morality?”:

Dawkins at 50m39s: “Some people find this prospect [of using instruments to understand the messages competing inside our brains] very frightening, very alarming – I think one of the most spectacular examples is the evidence that decisions are taken in our nervous system before we conciously know it, so when we decide to do something, little do we know that several seconds earlier we’ve already decided, which is another example of where science can actually get inside our minds better than we can, so to speak.”

Harris: “That actually torpedoes the whole notion of free will. I think you actually don’t need a notion of free will in order to have a notion of moral truth, and this is something that is very counter-intuitive to people. We know free will is a non-starter philosophically and scientifically. Now, many people struggle not to admit this, but however our mental life is caused, it is caused – either by prior causes or by some randomness intruding – but whether it’s purely deterministic or there’s determinate causes combined with some randomness, neither offer a space for free will to operate.

“Just imagine if all of your experience were caused by someone at a computer just determining what you feel and do and say and want. That’s clearly not a circumstance of free will. Now imagine if that person just was determining all that, but ten percent of the time threw some dice or introduced some other mode of randomness into the process. That doesn’t open up a space for free will.

“And we know, just as a matter of scientific fact, that everything you’re consciously intending to do, and wanting to do, and judging to be good or bad, is preceded by neural events of which you’re not conscious, and of which you are not the author. We walk through life feeling that we are the conscious author of our thoughts, but you can’t think a thought before you think it.

…

Harris at 53m56s: “And so what we condemn in an evil murderer is not the fact that he truly and really and metaphysically is the source of his actions – all these evil murders have either bad genes, or bad parents, or bad lives, or bad ideas, or some combination thereof, and they’re not the author of any of those things. But we still need to lock them up.

“When you go to death row and you interview the sociopath and you ask him, ‘What are you going to do when you get out?’ and he says ‘I’m just going to keep raping and killing people,’ that should make it pretty clear that you want to keep him in there. But we would keep earthquakes and hurricanes in prison if we could. And we would never think they’re evil earthquakes or evil hurricanes. Some things would change about our notion of retribution, say, but the idea that we would have to lock up killers is not one of them.”

When someone does something wrong we should change the incentives or perceptions thereof that made them do the wrong thing. And we should make the transgressed as whole as possible, yes, though we have to be careful not to pay too much attention to the dictates of their understandably strong emotions. If I could pick just one fact to inject into everybody’s heads14, it would be that emotions don’t make right. If you think they do, then why weren’t the lynch mobs right?

My tentative belief in innocence as a thing didn’t turn out to be “useful” for me – it didn’t stop me from getting raked over the coals about stupid stuff all the time. And that was the whole point – I kind of wanted to be innocent for the blamelessness, not for the ignorance. To get away from blame, I would have given almost anything. Being blamed sucks.

And yet inasmuch as people need to take responsibility for themselves as much as they are able, innocence is a bad deal. Innocence reinforces infantilism. Now maybe both are on a spectrum. But the more innocence you’re given, the less you’re recognized to be growing up. And of course there’s the blame-everybody-else danger:

“The innocent are so few that two of them seldom meet — when they do, their victims lie strewn around.” – Elizabeth Bowen

* * *

So why do we do the things we do? Says a friend with a psychology background: “Some people are objectively fucked up, and we need to unfuck them.” And sometimes it’s more of a failure or clash of philosophy, although that’s still built on biology, built on atoms, just like everything else. It’s weather with choice (perhaps two or more small weather fronts colliding) and meaning in it, but it’s still weather. On a certain level it makes as much sense to blame people as much as it does to blame the weather.

And what’s the moral difference between a physical powerlessness to do anything about your situation and a sensibility powerlessness to do anything about your situation? And if they knew better, why’d they do it anyway? What overpowered knowledge?15

There’s no argument for kids that’s not also true – at least to a degree – for adults. Yet for adults, if they commit a crime, they can go straight to hell as far as most people are concerned. We go out of our way to make their lives depraved and miserable. We don’t even let them on the internet. We can read the words of would-be jihadists16, get the latest updates from the Korean Central News Agency, and boy oh boy can we ever hear from Conrad Black17, but we can’t readily engage with most people convicted of consensual “crimes”. (Nor hear first-hand, in the moment, if it’s really so dangerous to drop the soap in the shower. I suppose, though, I could send Marc Emery an e-mail.)

I’m sympathetic when it comes to people who have lashed out at our critical institutions. You probably don’t want people orchestrating movements. But I’m generally tempted to say, look, let’s deal. Do we really think someone who robbed a liquor store is going to start a blog and convince us he did the right thing? I mean, we might be stupid, but are we that stupid? … … Okay, I mean, are enough of us that stupid? As for the Justin Bourques, well, maybe we could have a rule that if there are killings involved there’s a kind of e-parole process you have to go through, and of course you can’t use it to orchestrate further rebellion / insurrection. And you wouldn’t have the same or even any of the privacy expectations that someone on the outside would.

And, you know, a few hours on Khan Academy a day might do some folks a lot of good, and brain training in general might even make you more receptive to moral imperatives or more equipped to wrestle with moral philosophy.

I think the biggest risk of allowing incarcerated persons on the internet is that it would humanize them in a way that retributionists would find intolerable. I can totally see the outrage that would erupt at the very existence of a justinbourque.blogspot.ca. It doesn’t even look to me like a hill worth dying on. Yet I’m not sure it’d automatically be wrong. Maybe he’d even implore fellow parareligious gun nuts to keep up on their sleep hygiene.

Speaking of, what about the people that we’ll oh-so-humanely exonerate later but whom for now we’re just not (yet?) prepared to tolerate?

Imagine a homosexual in the 1950s. Nothing personal, but it’s just not allowed – we can’t accept a reality in which homosexual acts are not crimes. In such cases, if we’re not willing to change our moral assumptions, perhaps we need thought preserves, or networks of microstates. It’s too much strain to cram hundreds of millions of people onto a single moral framework. It’s kind of like putting all of a wide country on the same time zone. Even religions can’t hold themselves together on that scale, let alone states. (And, yes, religions and states will go to the wall to preserve the illusion of their unity. I’m more thinking about how large you can be consensually.)

Yes, of course, it’s much better to advocate for acceptance of homosexuality, but wouldn’t it have been easier for everyone if they had been able to go somewhere else and conduct themselves without our molestation, and then we could see that we’re worried about nothing? Imagine you’re sitting in Halifax in 1950. A Pride parade isn’t exactly a realistic option. But I suppose a thought preserve isn’t a realistic option either, unless “live and let live” climbs way the hell up our list of moral imperatives.

In any case, what we can more straightforwardly do is build on the system we have now, but for God’s sake let’s take the nastiness out of it. Not to mean that I want to worship transgressors, I only mean to sanctify transgressors up to the level of other human beings.18 Not with all of the same rights or freedoms for obvious reasons, but with at least a certain inalienable basic respect. It’s part of the reason I’m trying to avoid using the word “criminals”. Also “victims”.19

I suppose I’m just manufacturing more political correctness by avoiding the word, but it’s hard to deny that when you say the word “criminal” there’s an emotional reaction. (And you know the politicians pushing tougher laws are sure as shit going to use that word.20) If you want to reason with people, you have to bypass the emotional reaction. Hence my well-meaning yet insidious wordcraft nominally of reason, combating their well?meaning yet insidious wordcraft preserving the ‘integrity’ of their emotion.

We have our work cut out for us. Our “Public Safety”21 minister, Steven Blaney, said this in Parliament:

“Our Conservative government believes that convicted criminals belong behind bars, which is why we are taking strong action to keep our streets and communities safe. We have passed more than 30 bills to restore balance in our justice system, and none of those measures were supported by the opposition.”

As the notable defense attorney, the late Eddie Greenspan and co-author Anthony Doob write in the National Post:

“Unfortunately, the Public Safety Minister was not speaking off the cuff when he made his remarks. They are a faithful reflection of what the [CPCs] believe. Earlier this fall, Prime Minister Stephen Harper took credit for reducing Canada’s crime rate, saying, ‘We said “Do the crime, do the time.” We have said that through numerous pieces of legislation. We are enforcing that. And on our watch the crime rate is finally moving in the right direction; the crime rate is finally moving down in this country.’

“We plotted Statistics Canada data on the overall crime and the homicide rates since the early 1960s. Total crime peaked in the early 1990s when Brian Mulroney was prime minister and declined thereafter. It would be more logical, though wrong, to give the credit for our falling crime rate to prime ministers Kim Campbell and Jean Chrétien. Homicide specifically peaked in 1977. Attributing the drop in Canada’s homicide rate thereafter to the 1977 abolition of capital punishment would fit the data better than Mr. Harper’s explanation, though it, too, would be wrong.

“Mr. Harper became prime minister in 2006. For Mr. Harper to say that on his watch ‘crime is finally moving in the right direction’ is either blatantly dishonest or breathtakingly ignorant. With the attention that his government has given to punishment, we suspect he is not ignorant. As former New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly bluntly remarked ‘Taking credit for a decline in crime is like taking credit for an eclipse.’

“Imprisonment is certainly appropriate for some offenders. But it is worth examining two arguments that are often made for imprisoning offenders who could be punished in the community. Some believe that crime will be deterred if punishment severity were increased. Scores of studies demonstrate this to be false. This is inconvenient for Mr. Harper since many of his 86 so-called “crime” bills (33 of which have become law) are based on the theory that harsh sentences deter. Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, understood deterrence better than does Mr. Harper. Macdonald noted that ‘Certainty of punishment … is of more consequence in the prevention of crime than the severity of the sentence.’ Mr. Harper, who could benefit from empirical evidence, chooses instead to ignore it.

“Some believe that offenders learn from imprisonment that ‘crime does not pay.’ This, too, is wrong. Published research — some of it Canadian and produced by the federal government — demonstrates that imprisonment, if anything, increases the likelihood of reoffending. For example, a recent study of 10,000 Florida inmates released from prison demonstrated that they were more likely subsequently to reoffend (47% reoffended in 3 years) than an almost perfectly equivalent group of offenders who were lucky enough to be sentenced to probation (37% reoffended).”

Protection of the transgressed – individually and/or societally – from the transgressor is an additional purpose of imprisonment. But it doesn’t follow that we should make protecting and rehabilitating the transgressed come at the necessary expense of the fundamental rights of the accused and/or convicted. We learned these lessons at great length and great pain. But “Justice” minister Peter MacKay apparently thinks he knows better, or he recognizes that sacralizing “victims of crime” is an effective appeal to emotions and will be an effective talking point with many voters in 2015. Among other changes, you might not be able to face your accuser for certain charges, and you can be forced to testify against your spouse.

Writes Catherine Latimer of the John Howard Society in the Toronto Star:

“The problem … with the planned Victims’ Bill of Rights is its announced commitment to ‘restore victims to their rightful place at the heart of the justice system’ and to put the ‘rights’ of the victims before the rights of the accused. This threatens to roll back more than 500 years of progress in criminal justice.

“It was the hallmark of the primitive legal systems of the ancient world and medieval Europe that the wrongdoer and the person harmed stood at ‘the heart of our justice system.’ All injuries, whether accidentally or intentionally inflicted on people, were answered by vengeance, usually delivered by the victim or victim’s family. The revenge of victims was seldom just, inspiring renewed vengeance by the criminal against the avengers. In this barbaric system of victim against victim, European justice degenerated into a chaos of vendettas.

“The answer was to convert vengeance into a system of fines to be paid by the criminal or the criminal’s family for each type of injury. Criminal law was still a system of victim’s vengeance, though at least now it had some structure. But any idea of justice was missing, since it is clearly immoral for people to pay blood money to buy off their victims for the wrongs done to them.

“One of the greatest innovations of the criminal justice system was the realization that the wrongful injuries people inflict are primarily offences against the public moral order represented by the Queen, not just particular harms to individuals in a given situation. The notion of crime as a moral affront to be answered by a public trial rather than a private feud, and as an offence to public value rather than to private interests, divides primitive from modern justice.

“The present government’s plans for victim-centred justice forgets this lesson of history and threatens a slide back into a new dark age where victims’ vengeance poses as justice.”

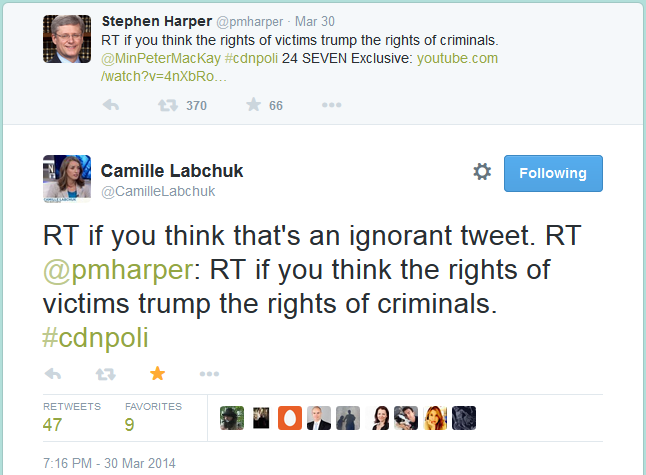

RT if you think… (Tweets by Stephen Harper and Camille Labchuck)

Dammit, it’s not a zero-sum game!22 Well, it might be seen to be one as soon as you sanctify the victims and encourage one-dimensional thinking. So let’s not do that! Vilifying transgressors and sanctifying the transgressed are related evils – it’s hard to take one without taking the other. It’s kind of like blame and innocence. In fact, it’s an application of blame and innocence. It’s appalling that many of our politicians are content to appeal to this cartoonish view instead of challenging it. Maybe they even believe it!

“Our government has been categorical: The justice system is going to be centred on the protection of society and the redress of victims. Our government will transform the justice system so that it is no longer centred on the welfare of criminals.” – Peter MacKay’s office, writing to the Ottawa Citzen

But maybe we shouldn’t panic. Steve Sullivan, Executive Director of Ottawa Victim Services, argues in iPolitics that it’s less than meets the eye, that the government did much less than it set out to:

“… the government heeded the concerns of critics who warned that fundamental reforms would change the justice system in ways that don’t serve the interests of the public — or the victim. The irony is that the government can’t admit it did the sensible thing. This is a party that takes pride in listening to no one but victims on the justice agenda. They have courted victims groups for the last decade and have said repeatedly they would put an end to a justice system that coddles criminals. If the Harper Conservatives admit that Bill C-32 really doesn’t change the system, how could they distinguish themselves from the NDP or the Liberals on victims’ rights?

“So they don’t admit it. They fudge the truth. They say the bill has enforceable rights — when it does not. They say it will change the system — when it won’t.”

So in the words of Sullivan, “It’s not the bill that is the problem, it’s the rhetoric”.

But let’s say you do believe in blame, and perhaps you even value retribution, perhaps as part of the deterrent. You could still be with me on this: Our moral understanding is always developing. And the rate, state, content, and trajectory of it differs for every individual.

And you can make generalizations, sure. But you know what happens with those – by definition, individual differences get overlooked.

Let’s say 95% of Canadian nurses are female23 and 95% of Canadian firefighters are male24. You might use this information to build proportionally appropriate staff washrooms in hospitals and fire stations, at least if you believe in having binary washrooms.

Okay, now imagine you have a combined hospital and fire station complex. Imagine that the builder decided to take a shortcut – the fire station’s staff washroom is a men’s washroom, the hospital’s staff washroom is a women’s washroom.

That’s bad. It’s convenient and it was based on a close approximation and it serves many more people than it doesn’t serve, and yet it’s somewhat unfair to the female firefighters and the male nurses as they have to go to another wing of the building to pee.

Heaven knows why we apply generalizations in the justice system. They’re injustice city. Because some can’t consent, none can. Because some Sex Offenders™ really did do horrible things, all are painted with the same brush. It’s ‘efficient’ (in generating misery, anyway) but it’s not fair. When it comes to making decisions of consequence, for God’s sake, stop painting with a broad brush! If what you really need is a scalpel, don’t ask for a shovel and promise you’ll use it judiciously.

Our government is also keen to cut off justice department research that was going in directions not in line with their ideology and by golly they will continue to be “tough on crime” come hell or high water.25 I think this ongoing wilful ignorance is the worst thing the CPC has done to us so far, and I mean that to be saying a lot, as there’s quite a list. The affirmation of criminalizing sex work might be a close second. Lagging on addressing greenhouse gasses seems like a more abstract and diffuse evil. Is a bit of pain for many worse than a lot of pain for a few, or the other way around? That’s up to you. In any case, our self-inflicted misery also comes with a literal price tag.

When “justice” policies have more people in jail for more time and risk making the country less safe, that’s a tangible, specific, particular evil. And they’re being wilfuly or at least instinctively-determinedly ignorant about it. I can’t blame them, as they are just following their incentives like everybody else – but for the sake of our collective well-being, into the pool with them. #abc2015

* * *

What to do about this? We’re stuck with the CPC until at least October. At the moment, I think the important thing is to create the space in our minds so that justice reform26 becomes politically feasible. That should, at least under a future government, free up the oxygen required for researchers and policy-creators to do their work and make the needed changes. Then, as always, we can move on to the new problems that fixing the existing ones creates. :-)

One of the most important parts of my intellectual toolkit are the contents of and ideas in Robert Sapolsky’s human behavioural biology lectures on YouTube. I highly recommend watching the whole thing over the next month or so of your life. Here’s the playlist27, and the books are Chaos: Making a New Science and Sapolsky’s own Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers.

But if you only have time for the moral of the story, here is the final lecture, on the theme of individual differences:

42:55: “So that’s one realm in which people are threatened by all the sorts of knowledge and where this is going in terms of describing the what-makes-us-who-we-are. There’s another realm, not just the what-happens-to-our-sense-of-self-ness – another realm of ‘What does society do with this?’ What does society do as we get more and more of these terms, and we understand more and more where the gears are, where the controls are, where the challenges are to the sense of autonomy and agency in people – what’s going to happen at that point?

“What’s clear is, if you are poor or poorly connected, you are screwed, because as more and more of these labels are given out, that’s just the excuse that’s needed to deny you a job, or health care, or fair housing – that is clearly an enormous danger with knowledge with this.

“But hopefully, what happens instead on a more optimistic note is, somewhere in all these continua that this class was about, you see, ‘There, but for the grace of God and a couple of neurotransmitters and three or four more receptors, could go I,’ as you begin to see a continua – as you begin to see all sorts of realms that are tragically done in biology – we have no trouble looking at a schizophrenic and seeing, ‘This is a disease, and this is someone who needs our care, and forgiveness, and protection,’ and we are in a world now where people who obsessively count numbers eight hours a day, we will have to be able to view that as just as much a disease that is just as much deserving of care and protection and understanding – with any luck, what all this knowledge is going to do is force us to extend an umbrella of protection, a realm of empathy into areas we could never have dreamt of before – would never have dreamt of, the same exact extent that if you took the wisest, most compassionate, most introspective person on Earth from 500 years ago and told them epilepsy is a disease, it would have made no sense at all. And we are certainly sitting here with a whole world of things where it could make no sense to us at all where we will come to see that it has biological components as strongly as any of these others and we will have this challenge of seeing that this is a realm not of judgement, but of protection.

“And when we reach that point, we will have discovered that when we describe somebody as being healthy – when we say we are healthy, what we’re really saying is, we merely have the same diseases that everybody else does. And with any luck, out of this will come a great deal of compassion.”

The difference between a disease and “normal behaviour” is a matter of degree rather than of kind.28 Pardon the tautology, but the biology is the biology – the biology that makes you cooperate here (it underpins the language and reason) makes you a violent person there (there was either no room for enough restraint to roost, or it was never there, or it was overridden). As Dilbert says, we’re moist robots.

Similarly: What’s an orientation, what’s a kink, and what’s a mental illness? The answer to that question still comes from social norms, though thankfully a few things have escaped the death grip of socially-blinkered psychology: Homosexuality was a mental illness until the 1970s.29 Will the world tolerate or (gasp) embrace more? Stay tuned.

In a way, I think if anyone is innocent, everybody is.

Everything?! ↩

Yes, the exact past that we had is the only way to this exact present. But what’s special about this present, aside from its being the one drawn from the Universe Machine? ↩

At a distance, unfortunately. I was afraid of being outed as liking girls and I went out of my way to avoid her. ↩

Or cement-head, if you’re less charitable. ↩

If you mean that kind of “innocence”, much later. ↩

If you’re interested in thumbing your nose at the prevailing attitudes, check out Free Range Kids. ↩

I don’t say “murdering” because murder means wrongful killing. The wrongness just seems so innate to it – I can’t imagine how you could pick up the word without it. ↩

If you’ll pardon my using the same categorical rhetoric I question; I mean to be facetious for the sake of a grin. ↩

If I were to do it single-handedly with just this post, that would be quite a trick. ↩

More on how we go out of our way to maintain our core beliefs:

David Dunning, Pacific Standard – “We Are All Confident Idiots” ↩Of the transgressed and the accused / convicted! ↩

For a profoundly moving example of forgiveness, listen to the story of Hector Black, part of a Radiolab episode on Blame. ↩

One fact for today. Next week I’ll want another. ↩

And again, I’m not saying don’t punish the stabby-stabby. The certainty of punishment is part of the knowledge that we hope will overpower such impulses. If you stab someone, you will go to jail. Or an equivalent this-will-rearrange-your-life-in-a-way-you-won’t-like. We just don’t need to make a big condescending political show about it. We desperately need to switch from prejudice to evidence. ↩

The CPC is probably going to make this the hottest thing since child pornography, so no link from me. ↩

Interviewed by Jian Ghomeshi, no less! ↩

We are such one-dimensional thinkers that this will be a tough row to hoe. Example: There’s an incentive for pot advocates to dismiss studies that suggest it can change your brain because if they don’t it lends vague legitimacy to helicopter pot patrols. ↩

I oppose the horrible abuser / innocent victim dichotomy, inasmuch as to put devil ears on one party and a halo on the other limits our thinking. Not to mention that certain victims can rationalize as much as abusers. And it’s demeaning to the futures of victims to rest everything on a fact of having zero agency. I’m not saying ‘blame the victim’ – as you’ll remember, I even happen to think blame itself is irrational! – but that doesn’t mean always-believe or always-affix-a-halo. They’re a party to a complex system, and there’s often a bit of a victim in an abuser and a bit of abuser in a victim. Reality resists devil ears and halos. Categorical thinking is a convenience that comes at the expense of nuance and detail… and, often, basic humanity.

Offer Zur – “Rethinking ‘Don’t Blame the Victim’: The Psychology of Victimhood” ↩

To some extent this is our fault – we’re the dummies that the media and politicians successfully manipulate. Writes Chris Alexander in his “Meditations on Moloch”:

“For example, ever-increasing prison terms are unfair to inmates and unfair to the society that has to pay for them. Politicians are unwilling to do anything about them because they don’t want to look “soft on crime”, and if a single inmate whom they helped release ever does anything bad (and statistically one of them will have to) it will be all over the airwaves as ‘Convict released by Congressman’s policies kills family of five, how can the Congressman even sleep at night let alone claim he deserves reelection?’. So even if decreasing prison populations would be good policy – and it is – it will be very difficult to implement.”

His blog is called Slate Star Codex and it is the greatest thing ever of ever. ↩

Now that’s a portfolio with a storied history. ↩

And the transgressor-society domain is laughably not, inasmuch as we’ve increased the suffering of the convicted without any tangible benefit to society – at the great expense of, in fact. ↩

Remember the faint hope clause? Also abolished in the face of inconvenient findings. ↩

The penultimate lecture, on the biological underpinnings of religiosity, wasn’t video-recorded. However, this video recording from a previous lecture series can be used as a substitute. It’s a 4:3 video stretched to 16:9 so you might want to play it in VLC or some other player that lets you fix that as you play it. ↩

My rewording of a statement in John Daikins’ summary of the lecture. ↩

Although maybe the power of taboo is more to, uh, blame than the inefficacy of psychology. Someday I should read about exactly how the thinking changed. ↩